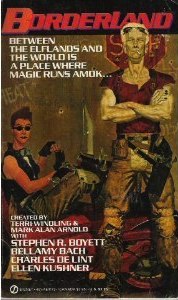

Welcome to the Bordertown reread, where I’ll be looking at each of the four original Bordertown anthologies, and the three novels set in that space between the Elflands and the World.

Or at least that’s what this will be most of the time.

Borderland, the first anthology in this shared world, was published in 1986, and was not the first Bordertown book I read. In fact, I had never been able to locate a copy until recently, so this isn’t a reread, but a first read.

The first story is Steven R. Boyett’s novella, “Prodigy.” “Prodigy” may be vintage Boyett, but it feels very little like Bordertown. Without the context of the anthology, that’s not the place on the map I would have put it. We’re told it’s set “six years after the return” while the other stories take place “many years later.” The temporal gap serves to explain why none of the people or places we encounter in this story are familiar.

Scooter is a musician, and the return of the magic to the places along the Border has given his playing power beyond the usual bonds of artistry. A chronological man who has never managed to grow up into an actual one, he uses that power in an act of hatred and revenge. Disaster is averted through the timely assistance of a group of people who are, I think, supposed to be elves or some type of Fae, but who read as plot device Magical Minorities, and the ending of the story is unfortunately pat.

With Bellamy Bach’s (a shared pseudonym used for Bordertown stories) “Gray,” the anthology moves into Bordertown proper, both the world, and the expectations guiding it. “Gray,” Charles de Lint’s “Stick,” and Ellen Kushner’s “Charis” all take place in the world described in Farrel Din’s Introduction. Din, the elf who owns the popular bar, The Dancing Ferret, describes the Borderlands as a place where elves and humans mingle in an uneasy truce, and neither magic nor technology works reliably, or as it ought. He’s right, of course, but people go there anyway. We will always go there anyway.

As these stories walk us through Bordertown’s streets, as the names of the bars and of the bands that play in them become recognizable, as we learn the gang affiliations of the Bloods, the Pack, and the Rats, certain other things begin to come clear. The first is that Bordertown is as much of a character in these stories as any of the humans, elves, and half-bloods that walk their pages. The Borderlands are as alive as any of those who dwell in them. The place matters: the setting guides the story.

The other is that the place doesn’t matter in the least. Running away to Bordertown—or being born there in the first place—won’t solve your problems. Proximity to magic, whether elven or otherwise, won’t make your life inherently magic. Where you are has no bearing on who you are.

The magic Bordertown is that it is a catalyst for self-discovery. Gray learns what she is, and that she must cross the Border into the Elflands to discover what she might become. Manda, from de Lint’s “Stick,” discovers what kind of guardian magics can and cannot hold their power in the face of scrutiny, and where her own role as guardian might be, and Kushner’s Charis, with her troublingly deceptive appearance, learns the bitter consequences of illusion.

And in each of these stories, Bordertown is built. We learn that Tam Lin is sung differently in the Elflands, the name of the dancing ferret who becomes a namesake for a bar, that even if you are Bordertown born, “if you’re born ordinary and clumsy you might as well come from East Succotash for all the good it does you.”

And still, people find their ways there, looking for answers, wishing for magic. There are other Bordertown books, other stories, other people who wish that there will fix all the problems of here.

“Charis” ends with a gift: a lock of elven hair and a silver ring, placed inside an elven box. There is a mirror in the lid. It is an ambiguous gift, and an edged one, and it is the perfect ending to this first collection. Because Bordertown itself is ambiguous and edged, full of beauty and of remembered pain. And its meaning is best divined by looking in a mirror.

Kat Howard‘s short fiction has been published in a variety of venues. You can find her on Twitter, at her blog, and at Fantasy-matters.com. She still wants to live in Bordertown.